Why Near-Critical Physics for Dense Phase Models Can Make or Break Simulators and Leak Detection Models?

Near the critical point, physics is not merely nonlinear, it is unforgiving. In this regime, small modeling shortcuts do not result in small errors. They can easily cascade into double-digit inaccuracies in the thermodynamic properties that underpin a leak detection system or simulation model.

This matters because dense-phase pipelines (particularly those transporting CO₂, Ethane, and similar fluids) often operate precisely in or near this sensitive region. When the physics is mishandled, leak detection performance degrades exactly where it needs to be most reliable.

Below, we outline the core challenges that make near-critical modeling one of the hardest and most consequential problems in real-time leak detection and simulation tools used for design studies.

Near the critical point, physics is not merely nonlinear, it is unforgiving. In this regime, small modeling shortcuts do not result in small errors. They can easily cascade into double-digit inaccuracies in the thermodynamic properties that underpin a leak detection system or simulation model.

This matters because dense-phase pipelines (particularly those transporting CO₂, Ethane, and similar fluids) often operate precisely in or near this sensitive region. When the physics is mishandled, leak detection performance degrades exactly where it needs to be most reliable.

Below, we outline the core challenges that make near-critical modeling one of the hardest and most consequential problems in real-time leak detection and simulation tools used for design studies.

Far from the critical point, thermodynamic properties behave politely. Density, heat capacity, and related parameters change almost linearly with pressure and temperature. In those regions, even approximate equations of state (EOS) perform reasonably well.

Near the critical point, however, the behavior changes dramatically.

For CO₂, Ethane, and similar fluids, the rate of change of properties becomes extreme. Small variations in pressure or temperature can cause disproportionately large jumps in density or in the heat-capacity ratio (γ). The property curves bend sharply, and linear intuition fails.

Most conventional equations of state (EOS) and tabulated property libraries were not designed to resolve this sharp transition. Data points near the critical region are often coarse, and interpolation schemes tend to smooth out the very physics that dominates the behavior. When a real-time model queries these routines, it may receive density or heat-capacity values that are off by 10%, 20%, or even 30%.

At the thermodynamic level, that error is already significant. In a leak detection context, it is only the beginning.

Real-Time Transient Models (RTTMs) rely on accurate fluid properties to compute fundamental quantities such as:

If density or γ is incorrect, the RTTM will predict the wrong wave speeds and the wrong transient response. Pressure waves arrive at the wrong time, with the wrong amplitude, and with distorted shapes. As a result, true leaks may be missed, while operational events may be falsely classified as leaks.

In other words, thermodynamic inaccuracies do not stay isolated. They propagate directly into leak sensitivity, reliability, and false-alarm performance.

Hyperbolic RTTMs impose a strict numerical constraint: the time step is tied to the spatial grid and the local speed of sound. In dense-phase lines, this often forces extremely small time steps.

The consequence is a very high sampling rate and therefore a very large number of thermodynamic property evaluations per second.

If each property call relies on a heavy, poorly behaved equation of state operating near the critical point, the system pays twice:

The problem is compounded by the reality of pipeline operations. Real pipelines do not stay in a single regime. Dense-phase operation in summer may transition into gas or two-phase conditions during cold shut-ins, followed by startups that introduce elevation-driven vapor pockets.

If the model applies one simplified logic for running conditions and a different one for shut-in or restart, it becomes most fragile exactly at the regime transitions. Ironically, those transitions are also the most diagnostically valuable periods for leak detection.

The challenge is not simply that near-critical physics is difficult. The deeper challenge is architectural.

Leak detection systems need a single, dense-phase-ready modeling framework that can handle CO₂, Ethane, and similar fluids across all operating modes such as steady operation, shut-in, restart, and regime transitions, without breaking the physics or compromising detection performance.

That means:

Only with this level of rigor can leak detection systems remain accurate, reliable, and trustworthy in the very conditions where failure is least acceptable.

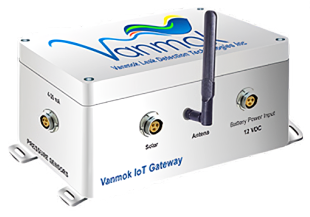

Vanmok Leak Detection Technologies helps operators and engineering teams address this risk early and systematically through the Vanmok CO₂ Simulator.

Our simulator is purpose-built to model dense-phase CO₂ pipelines across all operating regimes, steady state, transients, shut-ins, restarts, and regime transitions, without breaking thermodynamics near the critical point. It enables teams to run high-fidelity what-if scenarios such as:

By applying physically consistent modeling upfront, companies can reduce design uncertainty during FEED, avoid fragile assumptions in operations, and deploy leak detection systems with confidence in real-world conditions.

If you are designing, operating, or regulating CO₂ pipelines and want to understand how near-critical physics truly impacts safety and detectability, contact Vanmok at 780-989-1286 or info@vanmok.com to discuss how the Vanmok CO₂ Simulator can support your FEED studies, operational readiness, and leak detection strategy.

Near-critical physics does not forgive shortcuts—but the right modeling framework can turn it into a competitive advantage.